#10 Don’t turn the table. Flip it.

Note: This is the tenth post of the book after the introduction. If you’re new to the book, start with the introduction. Or visit the full table of contents.

The way you structure your business is massively important to maintain purpose for the long-term. Not just team structure, oh no, there’s more to it. If you’ve slogged through getting your idea to market, managed to survive in that market and are profitable enough to scale (or just got a load of investment) you should pay business structure some mind. In #9 Design a kickass team we talk about how structure is sometimes forgotten in the rush to scale and make those dollar dollar bills y’aaall. Scaling requires a lot of forethought and no small amount of planning, which can be the anti-powers of lean startups, it’s why they lean on ‘business advisors’, who advise them to do what’s always been done. And so creates the same problems, over and over again.

How you measure success defines behaviour yes? We established that wealth equals success in the aptly named #3 Success defines us post. Traditionally business has been a slave to business performance measured in revenues, in profits and the profits are those of the shareholders. Well, we need to flip this value creation on its head to get anywhere. Why? History has the answers, almost always. Let’s have some history then, which can be entirely attributed to Rebecca Henderson. Rebecca is a prominent economist and university professor at Harvard Business School. I’m a MASSIVE fanboy. With her book last year ‘Reimagining Capitalism’, Rebecca built an infallible, global business case for sustainability and purpose. We’ve been occasionally pestering her over email to come and do something with us in future events (ohhh, we’re starting events, that’s new!). She sometimes takes time to reply to our nagging asks and I reckon one day we’ll convince her to come play. Here’s hoping. Thanks Rebecca ✊ we love you.

Maximising shareholder value is bad

A story told by Rebecca: In the US in the early 70s, after the post-war era there was an economic downturn. The state had gained much wider control over the markets to rebuild after WWII and social cohesion was strong with a wartime ‘we’re all in it together’ mindset prevailing. A bunch of economists widely known as; The Chicago School of Economics suggested that the economic stagnation was because managers were putting their own well being ahead of their investors. Milton Friedman, the most prominent voice of the Chicago school and his peers, suggested tying executive compensation to shareholder value, to catalyse the markets and free them to pursue profits above all else. Across the board, corporates tightly linked CEO pay to the value of company stock. GDP growth went mental, shareholder value jumped and every CEO jumped for joy when they checked their bank balance.

“

There is one and only one social responsibility of business, to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits”

Milton Friedman — Economist

Over the coming decades the wealth of the top 10% in the US and UK economies (Friedman was also an advisor to Maggie Thatcher) grew exponentially, whilst for those at the other end of the scale, wages and wealth growth stagnated. All the while the huge environmental impact of large scale industrial activity was left unseen and unchecked. We now know that these hugely damaging impacts of business are unsustainable and we’re fast approaching the point where they’re irreversible. And you don’t want to be in a world where 1 billion people are displaced because of climate change, nations are fighting for scarce resources and everyone is fearful of the end. What do you think that does to the market? Hmm? Probably more of the above to be fair, the rich win, everyone else dies.

Milton Friedman was a smart man, no doubt. His argument that a competitive free market economy could provide results like no other model were compelling. Checkout his explanation using a graphite pencil:

Rebecca points out that the free market only works, if it is genuinely free and fair. Sucks to say it, but this is not the world in which we live. If businesses can dump toxic waste, control political process and get together to fix prices. Yeah, it doesn’t work. Essentially, to quote Rebecca again “markets need adult supervision”.

You can apply the above statement to business design. Yes, you want autonomy, co-creation and a lack of hierarchy, but what happens if no-one does what they’re supposed to, the loudest voice in the room dominates the debate and the biggest bully takes control? You need supervision. Think about businesses you’ve worked in, tell me you haven’t seen all three played out — sometimes they are the day to day experience for employees. That’s toxic. You have to design a business culture else it’ll happen organically anyway (Alex Barker from Be More Pirate said that almost verbatim yesterday in a workshop we participated in. Just sayin’). Also, do the toxic outcomes above remind you of any recent leader in particular? Not doing their job, loud, bullying behaviour, anyone? Hint, orangey tint…

Not massively relevant, I just wanted to bash trump and I like the picture

Fairphone as a counter to Milton’s pencil

I waxed on about Fairphone in the last chapter, but they really are fascinating. I’m fascinated because firstly their theory of change seems to map to ours (great, more on that in a second) and so do their values. Like; change can’t begin without education (yup), they’re purpose driven, sustainable and believe in open principles. Dreamy.

Fairphone is a sustainable phone, made from fairly sourced and recyclable materials. You can take it apart and replace bits yourself. There are over 300 components in the ubiquitous mobile phone, the perfect example of complex global supply chains and consumer demand that drives it, highlighted by Milton Friedman’s graphite pencil example. Many of these components are built from mined precious metals. One of which is Coltan. The mining practices associated with getting this one metal alone out of the ground, have contributed to millions of deaths. Here’s a wikipedia article on it.

The Fairphone social enterprise is both mission and product, what do I mean? Well, their theory of change as their Head of Design mapped out to me goes like this:

- Create awareness in the supply chain — not with the consumer.

This has the greatest impact, like us, Fairphone believes industry is where a real difference can be made. A global, competitive free market as Milton points out has complex ecosystems of supply and to truly redesign business and have impact, you have to consider these.

- The phone itself is the example of change.

Like a path-finder or proof of concept we’d run with a business to prove out a new way of working or business model, simply by creating the phone Fairphone proves that the consumer electronics industry can exist with a more sustainable model.

- Create a community and ambassadors for change

By being open in your mission and corralling others behind your purpose, you create momentum and ambassadors for change. Fairphone, by unpicking the supply chain, and making it more sustainable, light the way for others who use these same components in their products. They’ve created the Cobalt Alliance and now Tesla, Glencore and other giants of industry are creating fairer Cobalt mining supply chains.

Fairphone created an open source map of their supply chain, so you can see exactly where they’re sourcing and the relative complexity of the task.

Overall, they’re just fucking great really. The mining industry is a global killer. Aside from the Fairphone example, after water, concrete is the most widely used substance on earth. If the cement industry were a country, it would be the third largest carbon dioxide emitter in the world with up to 2.8 billion tonnes, surpassed only by China and the US. There is another way, people just have to give a damn and use it.

Is stakeholder capitalism good then?

Stakeholder capitalism is now wildly popular again and was even the focus of the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting, Davos 2020. It’s the idea that business meets the needs of all its stakeholders: customers, employees, partners, the community, and wider society. It’s not a new idea. It became widely accepted and widely implemented in 1932 when published in the dynamically named ‘The Modern Corporation and Private Property’, a book by Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means. After a few years of business trying to make it work, it didn’t take off. But as with almost everything, it was down to the way the idea was being put into practice, rather than the idea itself.

In trying to marry the vastly differing perspectives of so many stakeholders early attempts at stakeholder capitalism failed due to inertia. There was death by indecision. Dynamism disappeared. In this vacuum, with complete lack of clarity around objectives and with no clear purpose ‘Dilbert’ style managers appeared. Managers who made a career out of the disorganisation and stalemate atmosphere. People who are characterised in the famous Harvard Business Review Article, first published in 1977 (then republished many times): Managers and Leaders: Are They different?.

Dilberts:

- Focus attention on procedure and not on substance — so appearing busy, but really doing nothing

- Communicate to subordinates indirectly by “signals” — so they can’t be pinned down to a direct ask, so can’t be blamed for an outcome

- Play for time — because time is money, waste someone else’s and make money

I talk about Dilberts in this article from 2018, but referred to them as ‘the frozen middle’. Middle management who so often hijack change, whether intentionally or not. This complete lack of productivity from early attempts at implementing stakeholder capitalism got these businesses labelled Garbage can models. Branding eh, killed it.

Scott Adams’ famous Dilbert comic

So what is good then?!

When we set-up Po3 we knew we wanted to become a B-corp. B-Corps are not the final word in org design. A lot of people think they’re still tantamount to greenwashing. However, they do require you to amend your company articles and state that you will run the company for the stakeholders, not simply shareholders. It’s a legal requirement of being a B-corp. And rules, regs, the law IS a big part of creating sustainable purpose in business. You also have to look at your partners, your supply chain (important, see above), your policies on diversity, modern slavery and every other aspect you de-prioritise when you’re scrambling to make a buck. You also have to produce impact reports, so, from the off you’re going to need to measure this (see later on).

Employee owned businesses are another great example of moving the focus from revenues only. Decisions driven by people who actually work within the business are much more likely to consider; worker rights, equality and diversity as well as overall company values and purpose by their very nature. There are plenty of great examples of entirely employee owned businesses in the UK: Richer Sounds, John Lewis and Riverford as a starter. This is something we’re also considering ourselves as we grow and build other self managing teams, while still recognising the need for a global network of independent experts.

Obviously there’s a bunch of other models which aim for a much inclusive business design:

What do these models do that help them deliver purpose?

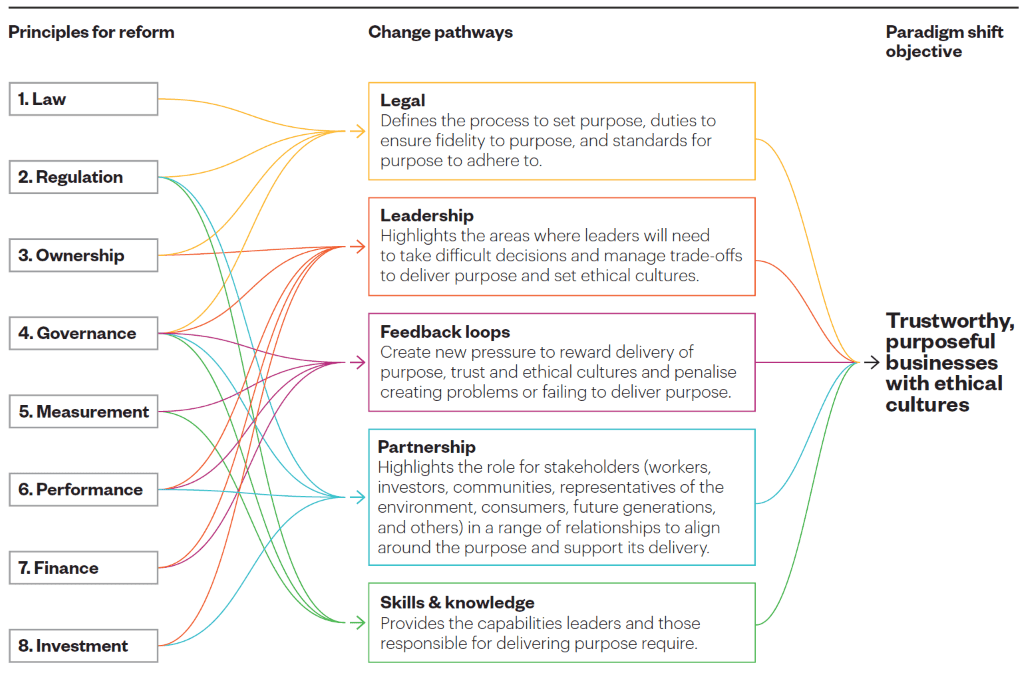

Right at the beginning, I said it’s more complex than simply having an idea and applying lean methods. Because as you grow, you have to think about balancing your mission, purpose and values with not only creating and scaling a viable business, but the needs of your colleagues, wider stakeholders and planetary needs. But it’s not very helpful to summarise like that, it’s confusing. So let’s clarify. The British Academy did an interesting piece of research into the principles for purposeful business, which are summarised in the image below.

Principles for purposeful business — The British Academy

The British Academy’s findings map pretty closely to how we work at Po3. Again it’s useful to simplify and correlate to the language we’ve been using throughout #TheFalseEconomy to see how:

- Legal — the way in which you incorporate your business, a B-corp etc.

- Leadership — the purpose you define in your mission values and behaviours.

- Feedback loops — running your business like a product, optimise, use data.

- Partnership — your ways of working and team design, how you get from ideation to delivery.

- Skills & knowledge — developing your people’s capabilities inline with business and personal needs ongoing, so everyone stays happy and productive.

Measuring purpose

Measurement, success metrics, KPIs, OKRs, they can either be employed for bad, or good. The simple ones, like — like how much money are we making are close to meaningless. They are a snapshot in time without context. They let you check the pulse while telling you nothing about underlying conditions, how those conditions occurred or what the future prognosis is. You can be dying and still have a perfectly strong pulse.

Bad measurements can drive negative behaviours, like having individual sales targets and commission structures. When you set individual targets like this, where’s the incentive to work with others? People won’t share information if it means someone else gets the money. People won’t collaborate on a proposal to create a holistic solution if they have no piece of the pie. People won’t think about the best way to deliver an outcome for a client or a user when they’re focussed on themselves. All toxic behaviours to avoid. Money generally makes people behave badly… Maybe this book could have been one line long.

Good measurements then, what are they?!

Good question. There is no one set. They’re based on each businesses proposition and purpose. First you need to define that purpose (see #8 Why do we exist?) and your: mission, vision and values. Based on these, you have something to measure. The next step should be to look at and measure these things:

- Inputs: the human, social, natural, physical and financial resources which a company uses in its activities.

- Outputs: a measure of what a company produces.

- Outcomes: changes brought about by a company’s activities.

- Impacts: consequential effects on the well-being of others, e.g. customers, employees, suppliers, societies and the environment.

For setting OKRs for various needs Google has some useful advice here as well as the history of OKRs and how they came to be. History is fun.

Then and only then, you need to measure the money. You need to monetise metrics because in business, resource allocation, investment decisions etc are all made by boards of companies, stakeholders, investors and by regulators and governments in evaluating the social benefits and conversely detrimental impacts. Not an easy task. Bet you wished you’d just jumped in an incubator, popped out an idea, got investment and accelerated to an exit. Yeah, that’s why we’re in this mess. In all seriousness, it’s not easy, so turn to Harvard business school as they have two routes:

- The first of these is an enterprise cost-based accounting approach.

This looks at monetisation from the perspective of the enterprise. Traditional cost-based accounting attaches specific and identifiable financial costs and revenues to inputs and outputs. In the context of corporate purpose, however, cost-based accounting would also need to account for the impacts of a company on financial and non-financial resources. It would record the costs that a company incurs in remedying the detriments it causes and the benefits it generates in relation to the externalities it imposes on other parties. - The second form of reporting is a societal valuation-based approach

This attempts to establish the impact of a company’s activities on society and the environment. 8 Traditional approaches to valuing purpose have focused on one stakeholder audience – shareholders. Where there are relevant goods or services being traded then there are observable prices with which to undertake valuations.

Here’s the paper for all the detail

It can be complex, but business is. More than that, life’s complex, whether you build a business or not. You may as well do something good, something purposeful.

“Life is hard. After all it kills you”

Katherine Hepburn

Bleak, Katherine, bleak. The truth is though — that it’s massively rewarding to find purpose in your working life, it’s why we’re in it for the long-term with Po3. Here’s Larry Smith, professor of economics highlighting some of the ridiculous reasons people invent not to pursue their passions. Blunt and funny. We like that.

Sign up for purpose

We're writing a book, a 'how-to' for the design and delivery of purpose driven, successful businesses.

Then we're giving it away, so anyone can use it.